Bilal, the Outrunner (Part-7)

Beginning with the previous six issues of Young Muslim Digest, the life of Bilal bin Rawaha, the famous Companion of the Prophet, is being serialized in this column every month. Presented herein under is the seventh installment in this series taken from the brief, but significant, biography by SYED IQBAL ZAHEER.

Adieu Makkah

Yet, and however evaluated in the heavens, even if that evaluation might have been a matter of great comfort, life was far from convenient for Muslims in Makkah. Persecution showed no signs of abating. In fact, it was getting worse by the day. Makkans were pretty panicky about the way Islam was spreading its influence in the Peninsula.

“What’s the driving force?” was a question they had so often discussed among themselves but had let the answer slip by them, for, as far as they were concerned, they had made up their minds: they’d hear the truth no more; they’d follow the truth never; they’d oppose the Prophet ever and ever.

This was not out of ignorance. Rather, not only had the message been clearly delivered – belief in one Allah, messengership of the Prophet, feeding of the poor, emancipation of the slaves, observation of chastity, non‑slandering of chaste women, and many other moral injunctions of the sort that no one can have a quarrel with – not only had this message been clearly delivered – the Makkans had, in the Qur’an and in its tremendous salutary effect upon its adherents, an additional sign.

None the less, the Makkans had made up their minds. They had made up their minds that they were not going to believe, sign or no sign. This incurred a sealing of their hearts: a doubly effective sealing as a result of which Islam would not enter their hearts, and Kufr would not find its way out. They had, in fact, gone one step further in disbelief. It was to oppose the truth and persecute its followers … and, audacity unbound, even persecute the Messenger of God.

This was evident right from the beginning; but they were given the respite of a whole ten years during which they could change their minds if the mind was the problem and not the ego. But, after a full decade of intransigence, not only had it become pointless to carry on with the call among them, but also some form of demonstration became incumbent that Divine Law of retribution existed and operated.

There was some indication of this – the impeding Divine punishment – when, as a first step, the Muslims were allowed to move to safer areas. They began to move out in batches. The first courageous lot headed for Habasha (Abyssinia): a place to which Bilal originally belonged. They were followed by several other groups.

Had Bilal chosen to go to Abyssinia, he would have joined a people of his own kind and felt homogenous among them. But he did not go. One thing was sure: he was not going to choose the place of migration based on such considerations. He had  broken all bonds with the un‑Islamic world.

broken all bonds with the un‑Islamic world.

Another reason for not migrating could possibly have been that he was not undergoing any special persecution lately, as in the earlier days. An added reason could have been that he wouldn’t want to part company with the Prophet.

Again, if he tarried for a while, it could have been because Makkah was dear to him. Finally, the Prophet (saws) might have not nodded a ‘yes’ to Bilal’s overtures.

Anyway, he didn’t seem to be in a hurry to leave the city. Even after having received a nod, he might have hung around hoping that something might happen: something that would allow him to stay back.

But that hope was fast fading and life was getting tougher. The best of Muslims were in Abyssinia. What few were left, were not only feeling lonely, but insecure to a greater and greater degree. Additionally, it was quite difficult to follow the Islamic practices. And, obviously, Islam was dearer to Bilal than the city, even if the city was Makkah.

Therefore, he finally decided to leave the city. It is also possible that the Prophet might have given him the hint to move out a little ahead of himself, for it wouldn’t have been wise for them to travel together exposing everyone to the same dangers.

One or two slipping out at a time would have made for their enemies organizing man‑hunts an unexciting affair. If the Prophet (asws) proved not to be lacking in organizational capabilities later in Madinah, surely he wouldn’t have let those qualities lie fallow unused at Makkah.

‘Muhammad at Makkah’ and ‘Muhammad at Madinah’ are two obtuse titles. Let alone a Prophet, even a man is a man. He is not transformed into a new and unrecognizable person with the crossing of five meters of land.

Nevertheless, Bilal spoke of his intention to Sa`d b. AbiWaqqas and `Ammar b. Yasir – the others of the batch that “were not proud.” They asked him to tarry for a while so they could join him. Sometime later, the three left the city heading for Madinah – then known as Yethreb.

A report in Bukhari has Bara’ b. `Azib as saying that the first ever to arrive at Madinah were Mus`ab b. `Umayr and Ibn Umm Maktum. After them Bilal, Sa`d and `Ammar. Surely, they would have left Makkah with heavy hearts. Up to a long distance, they would have turned again and again to cast a last glance at the beloved town, until it would have disappeared behind the familiar hills. And those familiar hills themselves would have disappeared behind the unfamiliar ones.

They would have trod on with heavy feet; hoping that something would happen suddenly and they would be called back. But nothing happened, they were not called back, and so they continued to march forward until they disappeared behind the craggy, barren hills.

They would have been terribly sad. But sometimes, to preserve your faith, you have to not only stand up against a lot of pressure, but have to also give up a lot in terms of comforts, a fat pay check, and “the town you are familiar with.”

Those who hang back, with material considerations in their mind, hoping against hope that something might happen and their children will never be “transformed” from the “innocent little ‘uns” of today into the “hedonists” of tomorrow with exposure to school and social evils, are not the ones that make the right choice for themselves and their families.

As Islam grows with sacrifices, one’s faith too grows with sacrifices. That’s how things work. It’s never a pleasant ride through an unhedged sycamore. “You shall surely ride upon event after event.” (Al‑Inshiqaq, 19)

The First Muedhdhin

In Madinah, Bilal was a host to Banu Sa`d ibn Khaythumah (c.f. Ibn Sa`d). We do not know what he did for his living and how he managed to meet with his everyday expenses, even if minimal. Surely, having been used to going about hungry so often at Makkah would have helped him a bit.

Yet, with so many new people constantly pouring into a place which was anything but a jostling commercial town, it couldn’t have been a joyous arrival for any. Neither were jobs easy to find, nor did other means amount to much.

Nonetheless, the main difference was the atmosphere. It was so fresh and friendly. Here the Muslims could go about in the town center and the fields without the fear of someone lurking behind looking for an opportunity to insult.

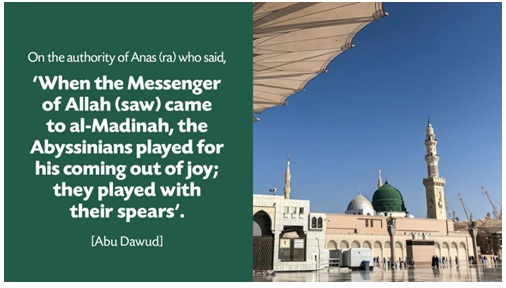

It wasn’t very long after Bilal’s arrival at Madinah that the Prophet also arrived, accompanied by Abu Bakr (ra).

Initially the Madinan climate did not suit the Makkans. Makkah was warm and dry. Madinan climate was comparatively moderate. But the winter was freezing. And wild winds blowing at storm speed would have chilled the ill‑clad immigrants. Many of them fell ill either because of the climate or, as some have thought, because of the influenza making its round.

Bilal also fell ill. So did Abu Bakr (ra). Both lay with high fever. It was in this state that the Makkan memories began to hound them lending their suffering a touch of acuteness.

When `Ayesha – Abu Bakr’s daughter – went to Abu Bakr (ra) to feel his pulse, and asked him how he felt, Abu Bakr (ra) recited a poetical couplet in reply in which he extolled death. She knew it was high fever that was speaking.

Abu Bakr said,

A man might be greeted by his family in the morning,

While death could be nearer than the lace of his shoes.

Next she went to `Aamir b. Suhayl, (the veil was not yet obligatory), and asked him how he was doing. `Aamir was also thinking of death. He recited the following lines in response:

I have experienced death before actually tasting it;

The coward’s death comes upon him as he sits.

Every man resists it with all his might,

Like the ox who protects the body with its horns.

After him, she went to Bilal. His lamentations of Makkan mountains, its valleys, its climate, its fresh and fragrant air… just everything… were no less heart‑rending. He said,

Shall I ever spend a night in Fakhkh,

With sweet herbs and thyme around me?

Will the day dawn when I come down to the waters of Majanna,

Shall I ever see Shama and Tafil again?

(Fakh is the name of a valley in Makkah. Shama and Tafil are surrounding hills. The translation of the poetical pieces above is by Alfred Guillaume)

At last, the Prophet prayed to Allah (swt) that Madinah be made as dear to the migrants as was Makkah, and to drive away the fever from the city to the mountains. This rendered Madinah more bearable to the immigrants.

After the construction of the mosque… a place to govern from… the first thing the Prophet (saws) did was to institute brotherhood between the Muhajiroon (immigrants) and the Madinan Muslims now called Ansar (helpers). Every immigrant was made a brother unto a helper. They were to share food and housing and were even to inherit each other. Bilal was made a brother to Abu Ruwayha.

After the construction of the mosque… a place to govern from… the first thing the Prophet (saws) did was to institute brotherhood between the Muhajiroon (immigrants) and the Madinan Muslims now called Ansar (helpers). Every immigrant was made a brother unto a helper. They were to share food and housing and were even to inherit each other. Bilal was made a brother to Abu Ruwayha.

Bilal never forgot the relationship instituted by the Prophet. Many years later when Bilal wanted to migrate to Syria, `Umar, the second khalifah asked him about whom he would authorize to collect his state‑allowances.

“Abu Ruwayha,” was Bilal’s answer.

Later, when he stayed back in Syria, he also took permission for Abu Ruwayha to live with him there. Hence, according to the historians, Bilal and Abu Ruwayha’s names remained registered together in the Syrian official books for a long time. (Al‑Bidayawa al‑Nihaya)

In Madinah also, as in Makkah, Bilal remained mainly attached to the Prophet. People would encounter him at the door of the Prophet’s house, as they went to see him.

They would see him with his shirt‑front spread and passing through rows of women‑worshippers during the `Eid Prayers to collect pieces of jewelry as charity.

They would see him holding silver in his shirt‑front and the Prophet (saws) scooping out of it and handing it out to the poor.

They would see him pitching a spear in front of the Prophet (saws) before he would start the Prayers, if he happened to pray in the open.

They could see him pitching a tent for him when they camped during the journeys.

They would see him carrying the standard (`Alam) when marching across, and handing it over to whom the Prophet would order.

They could see him leading the Prophet’s camel by its halter through the crowds of pilgrims in Hajj and shielding the Prophet (saws) with an umbrella when he alighted.

And they could hear him making announcements for the Prophet (saws) such as the one the Prophet (saws) ordered him to make after the Battle of Khayber when he was informed of a man who had fought bravely for the Muslims laying down his life, but had kept back a cheap unworthy article from the booty. Bilal was told to announce: “No soul, but that which has wholly surrendered itself to Allah (swt), shall enter Paradise. And, verily, sometimes Allah (swt) promotes the cause of His religion by a corrupt person.”

In fact, Bilal occupied such a rank with the Prophet (saws) that when `Abdullah ibn Ubayy, the arch‑hypocrite, spoke some nasty things about the Prophet and the Muslims, `Umar suggested that Bilal be sent to behead the hypocrite. (Haykal, The Life of Muhammad)

The incident also throws some hint about the muscle power of Bilal. Ubayy was no chicken.

Thus, where the Prophet was, Bilal was.

In one thing, at least, Bilal scored the distinction that no one else did. The Prophet (saws) used to, as a hadith of Nasa’ee tells us, lean on Bilal and deliver the `Eid sermons.

One can imagine what Heraclius, the last Byzantine Emperor, would not have felt like, on receiving the news of the Prophet (saws) leaning on Bilal, who had said to Abu Sufyan, “If I could see him, I would wash his feet.”

The services that Bilal rendered to the Prophet were of his own accord. No one, not even the Prophet, ever asked him to do anything for him. The Prophet (saws) was self‑reliant and avoided to be served.

On his part, the Prophet trusted Bilal and had deep regards for him. Once he saw Bilal in an angry mood and was told that his wife had refused to believe in something he had told her about the Prophet himself.

Instead of waving it away as a husband‑wife skirmish of little significance, he went with Bilal to his house, met his wife there and told her: “If Bilal reports to you something as what I have said, then that is what I have said. Bilal never lies.”

That was justice.

But he added: “Don’t provoke Bilal to anger.” (Ibn `Asakir)

That was love!

And a warning to those that do not know that there are grades, and levels, of the believers. Some occupy such positions that one will not anger them without risking the anger of the One on High.

However, and to continue, Bilal abandoned all else in life and devoted himself entirely to the services of the Prophet (saws). It was fitting, therefore, that he should be on hand to receive blessings, as it once happened during a journey.

It is said that a Bedouin came to the Prophet (saws) to remind him of his earlier promise to help him when he had something come his way.

“Glad tidings unto you,” the Prophet (saws) told him.

“Enough of these glad tidings,” the man said in impatience. “How long will you keep telling me, ‘Glad tidings?’”

The Prophet (saws) was angry. He turned to Bilal and Abu Musa al‑Ash`ari and said: “This man has rejected the blessing. So let it be the share of you two.”

He asked for a bowl of water, washed his hands and face into it and spat into it. Then he told the two: “Drink it. Sprinkle it on your faces and necks, and receive the blessing.” The two did as they were told.

Umm Salamah, the Prophet’s wife, who was accompanying him and was watching the proceedings from her tent cried out: “And the two of you, don’t forget your mother. Let her also have a share in it.”

They left some water in the bowl and passed it on to her. The report is in Bukhari.

In our times some people might wonder about what kind of a lady this Umm Salamah was. To many, perhaps, a simpleton over-anxious about benedictions. Over-anxious, true. Benedictions, yes. But simpleton?! Both, yes and no. People then were ever so simple, so yes. But if that implies that they didn’t understand complex things, then no.

Consider the following statement that declares the standard position of a Muslim about Asma’ wa Sifat (Names and Attributes) of Allah (swt). While many scholars, both ancient as well as modern, have stumbled, she (Umm Salamah) said in explanation of what is meant by the terms: Istawa `ala al‑`Arsh in the Qur’an: “Istawa is not unknown. Its ‘how’ is unfathomable (ghayr ma`qul), its acknowledgment (iqrarbihi) is (a part of) faith, and to argue about it is unbelief (Kufr).”(`Awn al‑Ma`bud, Vol. 13, p. 39)

If one cannot appreciate this statement, he may realize how little he knows of the wives of the Prophet (saws), and how little, indeed, of Islam.

A little after his arrival at Madinah the Prophet arranged for Bilal to marry a girl of his approval. It came about this way.  Some people of the Bukayr tribe came down to the Prophet seeking his help in getting a girl of theirs married to a suitable person. The Prophet (saws) surprised them by saying: “(I wonder) how you measure up with Bilal.” They got the hint, but apparently not agreeing to the match went away without answering. Perhaps their Arabism came in the way. Or maybe something else.

Some people of the Bukayr tribe came down to the Prophet seeking his help in getting a girl of theirs married to a suitable person. The Prophet (saws) surprised them by saying: “(I wonder) how you measure up with Bilal.” They got the hint, but apparently not agreeing to the match went away without answering. Perhaps their Arabism came in the way. Or maybe something else.

However, sometime later, they again broached the same subject with him but got the same answer. And, a little while later, perhaps having failed to find a suitable match, they spoke to him about it a third time. He gave them the same reply. But this time he was more forceful. He said, “(I wonder) how you measure up with Bilal,” and added, “(I wonder) how you measure up with a man of Paradise.” These words might have initially caught them off their guards, but they did help them get over whatever that had held them from accepting Bilal in the first place. (Ibn Sa`d)

One of the early injunctions at Madinah was about the Prayer‑call, the Adhan. Bilal, with his clear, piercing, and melodious voice was the obvious choice, although we can’t be sure if sonoric qualities were the main factors in the choice. However, the melancholic note in his voice softened the hearts hardened in the fields and markets. Abu Mah‑dhura and Ibn Umm Maktum were substitute Muedhdhinin. Ibn Umm Maktum also made the second Adhan of the Fajr.

According to a report in Ibn Majah, although declared weak by some traditionists, the phrase “Al Salatu Khairum min an-Naum” (Prayer is better than sleep) were added to the Adhan of Fajr by Bilal, and the Prophet (saws) endorsed its acceptance by not objecting to it.

Another report, also in Ibn Majah, and also declared a weak one, but which strengthens the above one, says that once when Bilal reported for Adhan of Fajr and he was told that the Prophet (saws) was still asleep, Bilal said these words twice: “Al Salatu Khairum min an-Naum,” and the Prophet (saws) let them remain added to the Adhan.

To Bilal, Adhan was not a mere religious obligation that was to be dutifully carried out. It was something he loved to do.  Over the years, he waited anxiously for each call‑time to arrive and looked forward to the next after the last. Reports say that normally he arrived much before the time and waited on the roof‑top for the dawn to greet him there. Yet, it is also reported that he didn’t follow this as a rule. Sometimes he delayed either the Adhan, or the Iqamah – probably following the circumstances of those reporting for Prayers. (Ibn Sa`d)

Over the years, he waited anxiously for each call‑time to arrive and looked forward to the next after the last. Reports say that normally he arrived much before the time and waited on the roof‑top for the dawn to greet him there. Yet, it is also reported that he didn’t follow this as a rule. Sometimes he delayed either the Adhan, or the Iqamah – probably following the circumstances of those reporting for Prayers. (Ibn Sa`d)

Once, he called out for the Fajr Prayers. But when the Prophet came out, he found that no one had turned up. “What has held them back?” he enquired. “(The biting) cold,” Bilal answered. The Prophet (saws) prayed that Allah (swt) drive away the cold from Madinah. However, what’s to be noted is that Bilal was there, undaunted by the weather.

Reports a woman of Banu Najjar: “Ours was the tallest house near the mosque. Bilal used to climb to its roof to make the call from there. He would come early and wait for the first streak of dawn to peep from behind the hills. When that happened he would stretch his hands and supplicate in the following words: `O Lord. I praise Thee, and I seek Thy help that the Quraysh take up the cause of Thy religion.’

“Never did it happen,” adds the lady, “that Bilal forgot these words before making the call.” (Abu Da’ud)

The words of supplication indicate Bilal’s deep concern for Islam. He prayed for its victory, but knowing that the Quraysh held the key to it, he prayed for their conversion, even though he knew well that those proud ones did not reciprocate to him in the same manner.

Sometimes, Bilal also hummed poetical lines as he rose up to call for the Prayers. Once he was heard singing:

What’s wrong with Bilal, may his mother lose him,

His forehead be wetted with blood.

The intent is unclear. But it could be that Bilal might have felt some pleasure at being honored to call for the Prayers from the Prophet’s mosque and sang that out loud by way of self‑reproach.

Some reports suggest that Bilal never delayed the call, though sometimes he delayed the Iqamah (the second call, inside the mosque, with which the Prayers start). Normally, he allowed sometime between the Adhan and the Iqamah. And then, when he knew it was time to start the Prayers, he would go to the door of the Prophet and say, softly, Hayya `Alas Salah, Hayya `Ala ‘l Falah … Salah, Ya Rasul Allah.

Sometimes he would sit right there at the doorsteps. When he saw the Prophet emerging from the inner door, he would begin to say the Iqamah (i.e., even before the Prophet had reached his place of Prayer).

Once, he was late in saying the Iqamah of the Fajr Prayers because `Ayesha (ra) had asked him to help her in something. When Bilal returned to the mosque, it was beginning to get bright. He called the Prophet (saws) for Prayers. When he emerged, Bilal, in his characteristic simplicity, told him that it was `Ayesha who had delayed him. The Prophet (saws) didn’t have anything to say about him, `Ayesha, or the delay. (Abu Da’ud, Salah al‑Tatawwu`)

Reports tell us that Bilal had a clear, melodious, deep‑toned and melancholic voice that reached the very hearts of the people. No wonder. For a well-called Adhan is as refreshing to the ear every time it is called out, as every new morning or evening bird song is. Adhan is never tiresome to hear. In fact, it has a strange effect upon the non‑Muslims too.

(To be continued)