Muslims of Tibet

Tibetan Muslims, in Tibet as well as those living in India, Nepal, Bhutan, US, Europe, Australia and Brazil, continue to cherish their hybrid identity which combines the Islamic faith and Tibetan traditions, writes PROF. A. R. MOMIN.

Tibet, the centuries-old traditional homeland of the Tibetan people, is now an autonomous region, officially known as the Tibet Autonomous Region, in the People’s Republic of China. The Tibetans are an ethnic group, with their distinctive language, religious beliefs and rituals, customs and traditions. The total population of Tibetans is estimated to be around 7.8 million. Of these, approximately 2.2 million live in the Tibet Autonomous Region and the Tibetan Autonomous Perfections in Gansu, Qinghai and Sichuan.

Nearly 189,000 Tibetans live in India, 16,000 in Nepal and 4,800 in Bhutan. The Balti people, who are of Tibetan origin and number around 300,000 are concentrated in Baltistan, Pakistan. There is a sizeable Tibetan diaspora, estimated to number about 25,000, in the US, Europe, Australia, Canada, Brazil and Mongolia. Following the annexation of Tibet by China and the persecution of Tibetans that followed in its wake, thousands of Tibetans migrated to India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Mongolia, North America, Europe and Australia.

The Tibetans speak the Tibetan language, which belongs to the Tibeto-Burman branch of the Sino-Tibetan family of languages. An overwhelming majority of Tibetans are followers of Tibetan Buddhism. Buddhism reached Tibet in the 7th century C. E. The Dalai Lama is considered as the spiritual and temporal head of Tibetan Buddhists.

Tibet and the Islamic World

There are references to Tibet in the works of medieval Muslim geographers and historians such as Yaqut al-Hamawi, In Khaldun, Albiruni, Tabari, Ibn Rustah, Yaqubi and Rashiduddin. Tibet was known to Muslim geographers and historians as Tehbat or Thebat. During the caliphate of Umar bin Abdul Aziz (717-720 AD), a delegation from China and Tibet came to the governor of Khurasan, with a request to send a Muslim preacher to Tibet. The governor sent Salit bin Abdullah al-Hanafi to Tibet for this purpose. This incident suggests that there was a small Muslim community in Tibet in the early part of the eighth century.

Following the conquest of Sindh by Muhammad ibn Qasim in 712, Tibet became a part of the expanding commercial network that linked India, China and the Malay Peninsula with the Islamic world. There were diplomatic, political and commercial relations between Tibet and the Islamic world during the Abbasid period. In the eighth century, the king of Tibet is said to have recognised the suzerainty of Caliph al-Mahdi (775-785). Gold began to be imported from Tibet from the 8th century, which was used by Muslim rulers for minting gold coins (dinar).

The unknown author of a Persian treatise, Hudud al-alam, which was written in the tenth century, says that there was a mosque in Tibet’s central city Lhasa, though the town had a small Muslim population. In the closing years of the 12th century, Muhammad Bakhtiyar Khalji (d. 1205), the ruler of Bengal, invaded Tibet and conquered some parts of the region. Some parts of Tibet lying between Badakhshan and Kashmir, including Baltistan, were conquered by Muslim forces at the close of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th century. Tibet was under the control of Qalmaq rulers, who were of Mongol-Turkish descent, in the second half of the 17th century.

Muslims in Tibet

China and Tibet are not only geographically contiguous but also share historical, economic and cultural linkages. Relations between China and Arabia predate the emergence of Islam. Chinese traders and merchants regularly visited the trading fairs in Arabia to buy and sell goods and merchandise. According to Chinese sources, an Arab delegation visited the Chinese city of Canton (Guangzhou) in 651 CE. Muslim historians say that this delegation was sent by the Caliph Uthman and was led by Sa’ad ibn Abi Waqqas, a Companion of the Prophet Muhammad (SAAW). He is believed to have built a mosque in Guangzhou.

The earliest Muslim communities in China and Tibet descended from Arab, Persian, Central Asian and Mongolian Muslim traders and soldiers who had settled in China’s southeast coast between the 7th and 10th centuries. Many of them married Chinese and Tibetan women, who converted to the faith of their husbands.

The Great Mosque of Xian, one of China’s oldest mosques.

Chinese society is characterized by substantial ethnic, religious, cultural and linguistic diversity. The Han Chinese comprise the largest ethnic group in the country, accounting for 91.59% of China’s population of over 1.35 billion. The Chinese government recognises 55 ethnic minority groups, which are officially designated as nationalities or national minorities (minzu). They are composed of nearly 120 million people and account for about 8.49% of the population.

Ten of China’s 55 national minorities follow Islam. These include Hui, Uighur, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Salar, Bao’an (Bonan), Dongxiang, Uzbek, Tajik and Tatar. The numerically large Muslim minority groups are Hui (10.5 million), Uighur (10 million), Kazakh (1.2 million) and Kirghiz (0.2 million). The Hui, who comprise more about half of China’s Muslim population, are mostly concentrated in the country’s northern and western provinces and have traditionally been farmers, shopkeepers and craftsmen. They are the descendants of Arab, Central Asian and Persian merchants who began arriving and settling in China since the seventh century. Many of them married local Chinese women, which resulted in their gradual assimilation into Chinese society. They generally speak Mandarin or other non-Turkic dialects.

An indication of the assimilation of Hui Muslims into mainstream Chinese society is provided by their “Sinified” names. Thus, Muhammad was transformed into Ma or Mu, Husayn into Hu, Sai’d into Sai, Shams into Zheng and Uthman into Cari.

Tibetan Muslims are of mixed descent. They have descended from Muslim men from Kashmir, Ladakh and Central Asia, who migrated to Tibet around the 12th century and married Tibetan women. In the 17th century, some Hui Muslims from Ningxia in mainland China migrated to Tibet and settled in Siling (Xining) in the northeastern part of the region. Many of them married Tibetan women. There is a Hui Muslim community in Lhasa, where they have their own mosque and cemetery.

Historically, Tibet’s Buddhist majority, particularly the religious leadership, has been very tolerant and accommodative of the religious and cultural identity and sensibilities of Tibetan Muslims. During the reign of the Fifth Dalai Lama (1617-82), Tibetan Muslims were granted substantial religious, legal, educational, economic and cultural rights. They had complete freedom to practise their faith without any interference or pressure from the government and to build mosques and establish Islamic schools. The Fifth Dalai Lama granted some land in Lhasa to the Tibetan Muslim community to build a mosque and to have a cemetery.

Tibetan Muslims had the freedom to elect a five-member council to manage and regulate their religious, legal, educational and cultural institutions. They were allowed to settle their internal disputes in accordance with Islamic laws. They were also exempted from the payment of taxes. In earlier times, during the Buddhist holy month of Sakadawa, the selling and consumption of meat in Tibet was prohibited. However, Tibetan Muslims were exempted from the ban. Muslim leaders were invited to attend all government functions.

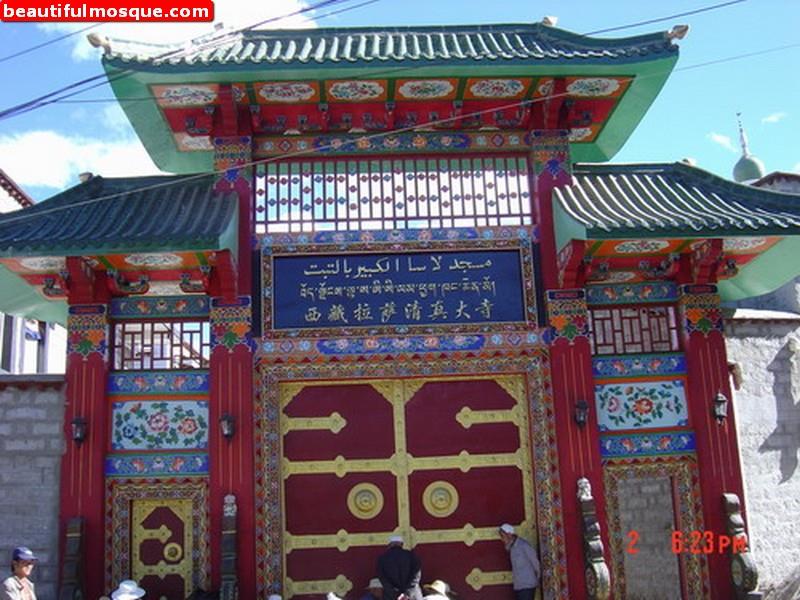

Central Mosque in Lhasa

The architecture of the Central Mosque in Lhasa reflects a synthesis of Central Asia and Chinese styles and motifs

As part of the Tibeto-Ladakh Peace Treaty of 1684, the Tibetan government allowed Muslim trade delegations from Ladakh to visit Tibet every three years. Many Muslim traders from Ladakh and Kashmir who came to Tibet as members of such trade delegations stayed on in the region. From the 17th century onwards, Muslim merchants from the Kashmir Valley had migrated and settled in Nepal. When Prithvi Narayan Shah, the ruler of Nepal, conquered the Kathmandu Valley and ordered the expulsion of Kashmiri Muslims, most of them migrated to Tibet.

In 1841 Kashmir’s Dogra army invaded Tibet but they were repulsed by the Dalai Lama’s forces. Many Kashmiri and Ladakhi Muslim soldiers from the Dogra army as well as well as Hindu Dogra soldiers were held as war prisoners by the Tibetan forces. Most of them stayed on in Tibet after they were set free. Some of the Hindu Dogra soldiers embraced Islam and chose to stay back in Tibet. Kashmiri and Ladakhi war prisoners introduced the cultivation of apples and apricot in Tibet.

In the wake of the Battle of Chamdo in 1951, Tibet was conquered by China. The previous Tibetan government was abolished in 1959 and Tibet was fully incorporated into the People’s Republic of China. The conquest of Tibet was accompanied by a brutal suppression of the religious and cultural rights and traditions of the Tibetan people. Tens of thousands of Tibetans, including Tibetan Muslims, migrated to India and found refuge in Himachal Pradesh, Kashmir, Ladakh, Kalimpong, Darjeeling and Gangtok. Around 2,000 Tibetan Muslims are living in Srinagar, the capital of Jammu and Kashmir.

Currently, around 4,000 Tibetan Muslims are living in Tibet and about half of them are concentrated in Lhasa. After the Chinese conquest of Tibet, the religious and cultural freedom and autonomy enjoyed by Tibetan Muslims for several centuries was severely undermined. There has been a systematic state-sponsored emigration of Han Chinese and Hui Muslims into Tibet, as a result of which the demographic composition of the region has substantially changed. Tibetans, including Tibetan Muslims, have been pushed to the steppes. Unlike the numerically Hui Muslims, who are officially recognised as a Muslim community or nationality, Tibetan Muslims are simply designated as Tibetans.

The Dalai Lama is the undisputed spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhists. Though Tibetan Muslims do not consider him as their spiritual leader, they hold him in high esteem. He, too, treats them with a great deal of affection.

Baltistan

Baltistan بلتستان) or སྦལ་ཏི་སྟཱན in Tibetan), also known as Little Tibet (སྦལ་ཏི་ཡུལ་།) is a mountainous area in the Karakoram region, which lies at the intersection of the borders between India and Pakistan. It borders Gilgit in the west, Xinjiang in the north, Ladakh in the south and the Kashmir Valley in the southwest. Medieval Muslim geographers and historians referred to Baltistan as the Little Tibet and to Ladakh as the Great Tibet.

Islam was introduced in Baltistan by an eminent Persian Sufi saint, Sayyid Ali Hamdani, or some of his followers in the 15th century. Until the middle of the 19th century, Baltistan was ruled by Muslim kings. It was conquered by the army of Raja Gulab Singh, the ruler of Kashmir, in 1840 and remained a part of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir until 1947.

After the ruler of Jammu and Kashmir acceded to India in the wake of the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947, Gilgit Scouts and irregular Pakistani troops invaded and seized Baltistan. Since then it has been a part of Pakistan and is now designated as the Gilgit Baltistan Autonomous Region.

The majority of people living in Baltistan are the Balti people, who are of Tibetan descent. They follow Islam, but remnants of centuries-old Tibetan customs and traditions as well as the Tibetan language still exist.

Tibetan Muslims: A Hybrid Legacy

Ernest Gellner, a distinguished British sociologist and philosopher and a keen and perceptive observer of Muslim societies, has remarked that a distinctive feature of Muslim societies around the world is the remarkable continuity and synthesis between the Islamic Great Tradition, exemplified by Islamic beliefs and ritual practices, the “Five Pillars,” a comprehensive legal and moral code and religious and cultural institutions, and the Little Traditions, represented by regional cultural traditions and practices.

The culture of Tibetan Muslims reflects a synthesis of traits, traditions and mores drawn from Tibet, Kashmir, Ladakh and Central Asia. This synthesis is distinctively reflected in the use of the Tibetan language, in the architectural style of mosques and in customs, dress and food habits.

For Tibetan Muslims, as for Muslims around the world in general, Islam is the primary source and mainspring of their identity. Individual and collective life among Tibetan Muslims is organised around the “Five Pillars” of Islam. There are four major mosques in Tibet, one in Lhasa, two in Shigatse and one in Tsetang. There are two major madrasas in the region, one in Lhasa and the other in Shigaste. Tibetan Muslim women generally wear the Islamic headscarf.

Ethnic and cultural identities are often multiple, hybrid, complementary and fluid. The process of hybridization of identities takes place over a long period of time. The process of identity formation is influenced by self-definition and choice as well by the perception, judgment and ascription by others. Therefore, a distinction may be drawn between self-identity and socially ascribed identity. Though these two dimensions of the process of identity formation are distinct, they are often fused.

In Tibet, Muslims are generally known as Kachee (ཁ་ཆེ), a corrupted form of Kashmiri, which alludes to the Kashmiri origins of Tibetan Muslims. In earlier times, the Kashmir Valley was known as Kachee Yul. Tibetan Muslims who are now living in the Kashmir Valley are described by the Kashmiri Muslims as Tibetans.

Tibetan Muslims, in Tibet as well as those living in India, Nepal, Bhutan, US, Europe, Australia and Brazil, continue to cherish their hybrid identity which combines the Islamic faith and Tibetan traditions.

[Reproduction Courtesy: www.iosminaret.org; Contribution Courtesy: Noor Muhammad Khalid]